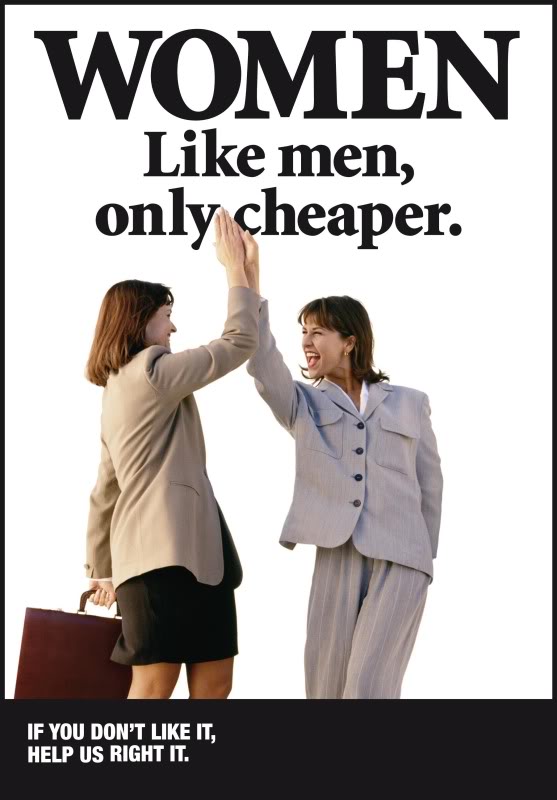

We have been told for years now that the gender pay gap between women and men is at about 77 cents on the dollar. However, what is more disturbing than this discrepancy itself is the fact that there has been relatively little change in this wage gap within the last decade (Blau and Kahn 8). The gender pay gap, which measures the average salary of male workers against the average salary of female workers, has existed forever. In a nation where women are now legally as free as men to work in whichever industry they choose, it is unclear as to why this discrepancy continues to exist. Of course, there are numerous variables to take into account when trying to understand the differences between men’s and women’s salaries, particularly within the same industries. The problem is that when you control for most, if not all, of these factors, researches have still found a difference that cannot be accounted for; it is likely that these differences are a result of gender stereotyping that causes both self-discrimination and gender discrimination.

Gender wage discrimination was not only legal in the US until 1963, but it was also not even considered an issue because parents and husbands were expected to shoulder the financial responsibilities of their daughters and wives (Perry and Gundersen 2). Right before World War II began, in 1940, women earned a meager “59 cents for every dollar earned by men,” (Perry and Gundersen 2). However, once the war began, many industries became saturated with women workers who replaced the men who had gone off to war. With many families now dependent on these women for income, “the National War Labor Board urged employers in 1942 to voluntarily make ‘adjustments to equalize wage rates paid to females and males for comparable quality and quantity of work,’ (Perry and Gundersen 2). Aside from this informal encouragement, not much else was done at the federal level concerning gender wage equality until 1963, when the Equal Pay Act was signed into law, which mandated that women and men be paid equally for comparable work (“The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” 20). The following year, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act outlawed employment discrimination based off of gender and other protected classes (“The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” 20). In order to enforce and regulate these laws, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP) were created and currently still investigate and bring litigation against employment and wage discrimination. More recently, in 2009, the government passed the Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, which strengthened the rights of employees who experience gender discrimination at work (“The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” 20). This legislation has no doubt helped women close the wage gap by eliminating blatant gender discrimination, but less obvious forms of gender discrimination have continued to persist and affect the wage gap.

There are numerous theories for why this gap still exists, but researchers have attributed it mostly to overcrowding, human capital theory, and occupational segregation. Interestingly, they have found that when the wage gap is adjusted for these contributing factors, it narrows to less than 10 cents (Corbett and Hill 21).

The overcrowding theory is purely economically based and asserts that “an excess supply of women in ‘female’ jobs depresses wages for otherwise equally productive workers (Solberg 129). In other words, because there is a greater supply of female laborers than demand for this labor in historically “female” occupations, the wage rate for these jobs is pushed down below where it would be if demand and supply for female labor were in equilibrium. While this has been considered a contributing factor to the wage gap, studies have found that it is not the “sole explanation of the gender pay gap,” (Solberg 139).

Rather, researchers see a much higher correlation between the wage gap and human capital theory, which states that:

Men and women provide differential returns to productivity. Women are paid less because they are less productive throughout their working lives than men due to differences in lifestyle factors (Strober 1990), including through having discontinuous work experience and part-time employment (Tharenou 200).

Human capital thus points out the disappointing truth that because many women must take time out of the labor force or work fewer hours to have children, they are paid less. Whether or not women are actually as productive as men after their return to the labor force, they are penalized for the simple biological truth that they are the only ones who can bear children. Of course, while it may be politically incorrect, the fact of the matter is that it is less risky to hire a man who an employer knows will never have to take time off to have a child than a woman who may or may not have to do this (Perry and Gundersen 5). Furthermore, from an economic perspective, it makes sense to invest in employees who can commit to working longer hours without interruption, and this helps to explain why we often see such few women in top leadership roles that take years of continuous commitment to reach. This theory is supported by a plethora of data. In 2010, the US Census Bureau found that the wage gap for women with children was 73.6 cents for every dollar men earn, lower than the average 77 cents for all working women (Perry and Gundersen 5). In fact, “the more likely a woman is to have dependent children and be married the more likely she is to be a low earner and have fewer hours in the labor market,” (Perry and Gundersen 5). The disturbing reality of this is that it does not seem plausible that this discrepancy will ever go away, since it is essentially impossible that there will ever be a time when women are not the ones who must take time out of the workforce to bear children.

Similar to human capital, occupational segregation also contributes to the gender wage gap in that women often choose occupations that are lower paying because these jobs either allow for more flexible hours, part-time work, or other benefits that allow these women to balance their professional and family lives. Many of these occupations are often denoted as “pink collar” jobs because female workers have historically dominated these industries. In other words, this phenomenon takes into account the fact that the gender wage gap is not only the result of economic realities but also the individual choices of women as a whole.

When adjusting for these three different theories, research has found that the wage gap then narrows to about a 7-cent difference between men’s and women’s wages (Corbett and Hill 21). In other words, we only understand about 16 cents worth of the wage gap between men and women. Just because we understand it though, does not mean that it is any less concerning than the 7 cents unaccounted for, particularly in respects to the fact that the effects we understand are still gender-linked and all interact with one another. Take overcrowding together with occupational segregation, and it is clear that many jobs historically associated with women are valued less than those associated with men when a number of these jobs arguably require similar skills or educational levels. Furthermore, when taking human capital into consideration, it is difficult to foresee women ever completely closing the gap when we are penalized for our ability to give birth. As a woman, it is truly frustrating to see that free-market capitalism and biological difference, both completely out of our control, cause us to be paid less than men. Even more frustrating is the fact that this implies that because of these unavoidable differences, women may never completely close the wage gap.

Of course, the unexplained portion of the gender pay gap is also of great concern because we cannot make progress toward closing the gap if we do not completely understand all the factors that cause it. While research in this area is still quite incomplete, researchers are primarily in agreement that gender discrimination makes up some component of this unexplained gender pay difference (Tharenou 202). We see evidence of this in the fact that there still continue to be court cases concerning employment discrimination based off of gender (Blau and Kahn 14). The Lily Ledbetter case, which led to the passage of the Lily Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, is a great example of this. Large corporations like Wal-Mart have also been accused of “systematic pay and promotion discrimination” when it comes to their women employees (“The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” 18).

While most of us acknowledge that gender discrimination still exists in employment practices, there are still disputes as to the extent to which this discrimination causes the unexplained gap in pay. Furthermore, it is unclear and probably unlikely that gender discrimination alone causes the entire 7-cent gap currently unaccounted for. What is clear is that the entire 23-cent pay gap is very closely linked to gender in one way or another. Therefore, it is logical to speculate that both the portions of the gender pay disparity that we understand and the portion that is still a mystery are rooted in a similar source.

Phyllis Tharenou and Hilary Lips make a very interesting argument to explain both the understood and misunderstood aspects of the gender pay gap: social psychological influences (Tharenou 202). There is no denying that our society is largely built upon the ideas and beliefs of men, so it is not a far stretch to conclude that societal influences and socialization have caused differences in valuing men’s work over women’s work. Except for a minority of men in America, it is unreasonable to believe that they all have a conspiracy to keep women down. However, we cannot discount the effect that living in a patriarchal society has had on the way women view themselves and view the world.

Lips argues that gender stereotypes about norms and expectations cause people to not only discriminate against women but cause women to discriminate against themselves (Tharenou 202). It is important to realize that both men and women discriminate against and stereotype women (Tharenou 202). In turn, Lips and Tharenou believe that this leads society to “uphold and maintain gender-linked social roles,” which then manifest themselves in the decisions that men and women make about their lives, and in this case, their occupations (Tharenou 203). Take occupational segregation or overcrowding, for example, which theorize that women are paid less because they choose to work in industries that are lower paying and often considered “women’s work.” Here we can see the direct link between Lips and Tharenou’s theory that stereotyping leads to wage discrimination. It seems almost intuitive that women would flock to occupations that have historically been filled by their sex because this is what they grew up understanding as work that women did, and after all, many of the women working in these “pink collar” jobs were the women who raised us. Furthermore, it is a stereotype in and of itself to say that there are occupations that are more suitable for women or that jobs that have historically been filled by women must be women’s work, when all of these perceived roles have been socially constructed over thousands of years. We can see how Lips and Tharenou’s theory may also affect human capital theory in the way that women often choose to take time off, leave the labor force, or work part-time in order to take care of their families. The stereotype that women are responsible for child-rearing and housework has persisted forever, and even now, many women still feel that these tasks are their responsibilities, despite the fact that they have the freedom to choose not to take on these roles. The bottom line is, to some extent, the way women choose to live their lives and the way their occupational worth is valued are all affected by pervasive gender stereotypes.

Tharenou points out that even if the effects of these stereotypes start off relatively small, they can compound over many years (Tharenou 204). For instance, numerous studies have shown that women are less assertive when it comes to negotiating their salaries, particularly their first salary out of school (Corbett and Hill 3). This is because women who show aggression, or any other “masculine” traits for that matter, “are evaluated more harshly than men especially when seeking, or when they are employed in, leadership roles,” (Tharenou 202). Here we have an example of first, how women are socialized to be less assertive, and second, how right from the get go they may not be receiving the salary they deserve. While this may start out as a relatively small discrepancy, it only gets larger over time as a woman’s salary compounds from this initial lower value, as she takes time off to have children, and so on. Essentially from the start, these women are dooming themselves to never be able to catch up to their male counterparts. In other words, while the effects of gender stereotypes and discrimination might be subtle at first, they have cumulative effects over the decades of one’s working life and thus end up increasing the wage gap between men and women as they age. There is data supporting this cumulative effect, which shows that from ages 20-24, the post-college years, the average female’s salary is about 93% of the average male’s salary, but by 55-64 years of age, the gap increases to only 75% (“The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” 12). While there is no direct evidence proving that this is a result of gender stereotypes and discrimination affecting gender wage inequality, this is a very plausible explanation for why we still cannot explain a portion of the gap, especially since it is extremely difficult to quantitatively measure the effects of stereotyping and discrimination in its more subtle forms.

Many who question the validity of the gender pay gap issue point to the idea that if we know that much of it results from women’s own personal choices, is the wage gap measurement actually relevant? Of course, all women should be free to choose whatever occupation makes them happy, whether that means one with less hours or one that pays less. The discussion of the gender wage gap should not in any way insinuate that these are invalid life decisions. However, not all women make professional choices based off of what makes them happy, but rather, most of them make decisions based off of economic necessity. Many women, especially single mothers, do not wish to work less hours or for less pay because they necessarily like their jobs, but they must in order to raise their children at the same time. Less time working and lower wages translate directly to what these women can provide for their children, and single women are the largest group below the poverty line in the United States (Cawthorne 1). It is therefore childish to flippantly dismiss the gender pay gap as an illegitimate concern. When one particular segment of the population is inherently more likely to live in poverty just because of their gender, there is clearly a disconnect within our society.

Women may be penalized in the workforce for factors beyond their control, but for those that we can control, we should be doing all we can to remedy them. First, women should push for compensation transparency, specifically in the private sector. If employers were forced to disclose compensation for all employees, there would be fewer disputes over gender wage inequality within the industries. Furthermore, legislation needs to be rewritten to place the burden of evidence less on the defendants in gender wage discrimination cases and more on the plaintiffs, for the laws as they stand make it very difficult for women to successfully litigate against workplace discrimination. Another innovative idea used in Minnesota is using “audits to monitor and address gender pay differences,” (“The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” 20). The state requires its public-sector employers to conduct studies every few years to “eliminate pay disparities between female-dominated and male-dominated jobs that require comparable levels of expertise,” (“The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap” 20). More evaluations like these would also help states and employers figure out where the largest pay disparities lie and thus allow them to address these specific issues. Lastly, further research must be done to investigate the direct effects of social psychological influences on the gender pay disparity (Tharenou 202). Until we can fully understand all of the causes of the wage gap, we will not be able to fully overcome it.

On a broader scale, we need a societal shift in perceived gender roles and discrimination. Until we get to a point were certain family roles and occupations are no longer associated with a single sex, we will not have pay equity amongst the sexes. We must not continue to perpetuate gender stereotypes as a society, but more specifically, women must take it upon themselves to defy these stereotypes. Truthfully, the complete closure of the gap may never come to fruition because of the biological differences between men and women, but there is certainly still room to improve. Once there is more equitable sharing of family and professional responsibilities between men and women, there will be further progress toward lessening the wage gap between them as well. However, when the majority of women continue to compromise their own lives with less compromise from their male counterparts, women’s wages will continue to be compromised as well.

Works Cited

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. “The Gender Pay Gap: Have Women Gone as Far as They Can?” Academy of Management Perspectives 21.1 (2007): 7-23. Print.

Cawthorne, Alexandra. The Straight Facts on Women in Poverty. Rep. N.p.: Center for American Progress, 2008. Print.

Corbett, Christianne, and Catherine Hill. Graduating to a Pay Gap: The Earnings of Women and Men One Year After College Graduation. Rep. no. 978-1-879922-43-3. Washington D.C.: American Association of University Women, 2012. Print.

Perry, Jennifer, and David Gundersen. “American Women and the Gender Pay Gap: A Changing Demographic or the Same Old Song.” Advancing Women in Leadership 31 (2011): 153-59. ProQuest. Web.

The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap. Rep. Fall 2013 ed. N.p.: American Association of University Women, 2013. Print.

Solberg, Eric. “The Gender Pay Gap by Occupation: A Test of the Crowding Hypothesis.” Contemporary Economic Policy 23 (2005): 129-48. ProQuest. Web.

Tharenou, Phyllis. “The Work of Feminists Is Not Yet Done: The Gender Pay Gap—a Stubborn Anachronism.” Sex Roles 68.3-4 (2013): 198-206. Print.

United States of America. US Department of Labor. An Analysis of the Reasons for the

Disparity in Wages Between Men and Women. Pittsburgh: CONSAD Research Corporation, 2009. Print.